October 9 is Hangeul Day (한글날) in Korea.

In Joseon Korea, literacy was a symbol of class. Only the Yangban aristocracy could afford to spend years memorizing thousands of Chinese characters and read the Classics. Commoners, peasants, and slaves were a voiceless majority.

Unsatisfied that ordinary people couldn’t communicate with him and each other in writing, King Sejong developed the Korean alphabet which could be learned by anyone regardless of their educational background.

As expected, the ruling class was not happy with this. They saw it as a threat to their status and relegated the Korean script to a lower class only for use by second class citizens. They called it the “vulgar script.”

As a result, the use of Korean characters became a revolutionary act to call out the injustices of those in power.

Some later kings banned the use of the Korean alphabet when they discovered documents criticizing them written by commoners.

During Japanese rule, Hangeul (which was coined during this period) was suppressed even further. After independence, there was a concerted effort to speak our language and to reclaim our national identity.

Now, Hangeul is and continues to be a symbol of Korean national pride. And today, illiteracy is virtually non-existent in Korea.

The Invention of Hangeul

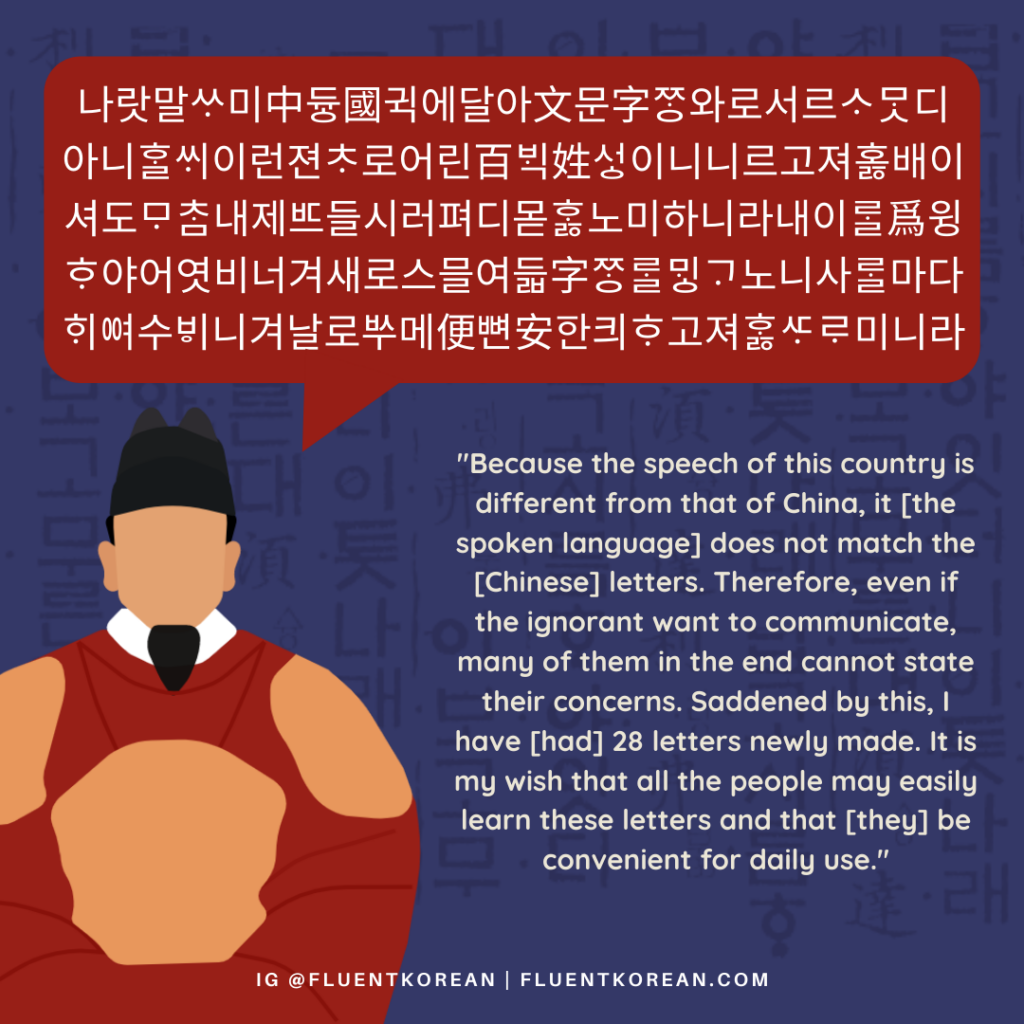

King Sejong the Great (세종대왕/世宗大王) invents the Korean alphabet. His objective is to improve literacy so people of all classes could make their voices heard.

The Promulgation of the Korean Alphabet

King Sejong promulgates it with the Hunminjeongeum (훈민정음/訓民正音) or The Correct Sounds for Instruction of the People.

Opposition to Korean Characters

Choe Manri (최만리/崔萬里) and other Korean Confucian scholars oppose the alphabet. They and other Yangban aristocracy see it as a threat to their social status.

Unlike commoners and peasants, the Yangban class can afford to spend years studying thousands of Chinese characters. Because of this, literacy is a status symbol.

They relegate Hangeul to a second class form of writing for slaves, peasants, and women and call it Eonmun (언문) or “vulgar script”.

The Korean alphabet becomes a revolutionary script used by those who are not in power to express themselves, to organize better, and most importantly, to call out the unjust actions of those in power.

The Korean Alphabet’s Popularity Rises with Commoners

The vernacular script becomes popular with women and other less formal writers.

Sijo poetry flourishes and a genre of writing emerges using the Korean alphabet in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Criticism of Those in Power

While King Sejong wanted everyone to be heard, the tyrant King Yeonsangun (연산군/燕山君) bans the study of the Korean alphabet in 1504, and King Jungjong (중종/中宗) abolishes the Hangeul research bureau, the Ministry of Eonmun in 1506, when they discover documents criticizing them.

Making it Official

Hangeul is used in official documents for the first time.

Hangeul in Print

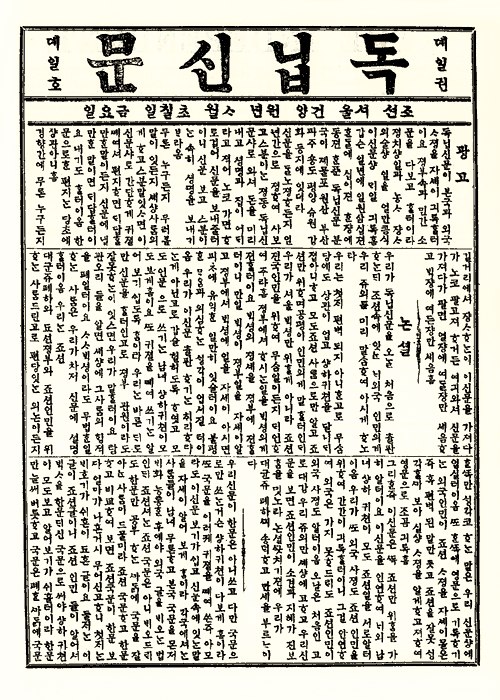

Tongnip Sinmun or The Independent (독립신문/獨立新聞) becomes the first newspaper to be printed in both Korean and English.

The Korean Alphabet Gets a New Name

Korean linguist Ju Sigyeong (주시경/周時經) coins the term Hangeul (한글) to replace Eonmun (언문) or “vulgar script”.

He also establishes the Korean Language Research Society.

Japanese Colonial Rule

Japan colonizes Korea and makes Japanese the official language.

As part of its cultural assimilation program, the teaching of the Korean language is banned from all schools in 1938 and all Korean-language publications are banned in 1941.

Korean linguists continue to make reforms during the colonial period.

Revival

Hangeul makes a revival after the end of colonial rule.

There is also a concerted effort to remove as much Japanese vocabulary from the common language as possible.

The definitive modern Korean alphabet orthography is published in 1946.

Hangeul is and continues to be a symbol of Korean national pride and identity.

Leave a Comment